Más Información

EU lanza ataque contra objetivos del Estado Islámico en Siria; Trump dice que es "represalia muy seria"

Clinton, Jagger y Michael Jackson aparecen en archivos de Epstein; pesquisa no es sobre el exmandatario, dice vocero

Corte Interamericana responsabiliza a México por feminicidio de Lilia Alejandra García Andrade; su madre ha luchado desde 2001

"Queremos cerrar este capítulo", dice Salinas Pliego al SAT; esperarán a enero a conocer fundamentos legales de adeudo fiscal

Marco Rubio destaca labor de seguridad de México; "están haciendo más que nunca en su historia", afirma

Hallan cuerpos en finca que ya había sido cateada en Silao, Guanajuato; suman 7 personas encontradas en menos de tres semanas

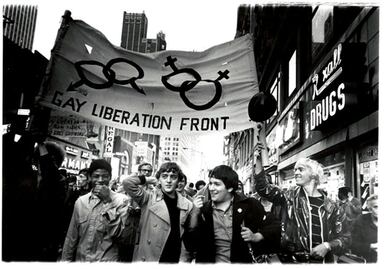

The number 41 has a secret meaning in Mexico and is closely related to homosexuality . Though it is often seen as a taboo and avoided in popular parlance, Mexico’s LGBT+ community has often used it to vindicate their sexual orientation and freedom. This year, Mexico’s Gay Pride March turns 41, making it a particularly special occasion that also commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots .

The story behind the number

On 18 November 1901 , during the presidency of Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911) a society scandal shook the country when police forces carried out a raid against a private home on Calle de la Paz (since renamed Calle Ezequiel Montes) in Mexico City’s Tabacalera neighborhood .

Several homosexual men had gathered to celebrate a private party, of whom 19 were dressed in women’s clothing. The police had received a complaint that there was too much noise coming out of the house. However, as soon as they saw men wearing women’s clothes, they proceeded to arrest them for “acting against morality and good customs.”

The press was keen to report the incident, but the government made efforts to hush it up, since some of the participants belonged to the upper echelons of society. It is rumored that Ignacio de la Torre y Mier , Porfirio Díaz’s son in law, was among them. While it is said that a total of 42 people attended the party, Mexican authorities allegedly ordered the press to report the arrest of only 41 people, in order to protect Ignacio de la Torre y Mier.

The dance of the 41 contributed to the visibility of homosexuality in Mexico, since it was the first time that the subject was addressed in the media. However, homosexual acts continued to be repressed in the country until late in the 20th century.

Both the incident and the number was spread through press reports, engravings, satires, plays, literature, and paintings. José Guadalupe Posada, the mind behind the famous Mexican Catrina , made engravings alluding to the affair, which were frequently published alongside satirical verses.

Some of the men arrested were moved to prisons, others were taken to military quarters, and another group was sent to Payo Obispo (Chetumal) , where they were forced to serve in the army for what was called the Caste War of Yucatán .

Those who remained in the capital were forced to sweep the streets in women’s clothes as punishment through public humiliation.

However, seven of them managed to avoid legal consequences by filing “amparo” appeals.

dm

Noticias según tus intereses

[Publicidad]

[Publicidad]