Más Información

Claudia Sheinbaum reabre segundo piso del Museo de Antropología; rinde homenaje a culturas indígenas y afromexicanas

Identifican a mexicano muerto en tiroteo en Consulado de Honduras en EU; evitó la entrada de migrante armado

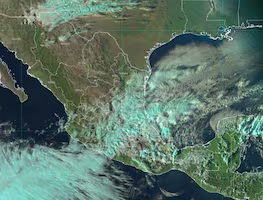

Frente frío 21 y tormenta invernal golpean México; alertan por caída de nieve, aguanieve y temperaturas bajo cero

A quick glance at inflation rates suggests Brazil and Mexico are not even in the same region; they appear to be worlds apart.

Brazil’s finished 2015 at 10.7 percent, the highest in more than a decade and well above the government’s target, even in the middle of an historic recession.

Mexico inflation is at a record low of just above 2 percent.

These inflation rates have taken completely divergent paths even as Mexico’s peso, just like Brazil’s real, sets record lows one session after another against the U.S. dollar.

A series of flaws in Brazil’s wrecked economy explains most of its inflation pressure:

-Salary increases have been granted by law with no strings attached, regardless of whether workers – and the rest of the economy – have grown more productive or not.

-Trade barriers have hampered competition.

-A ballooning budget deficit has led to a series of tax hikes and raised the specter of fiscal dominance – in which monetary policy has little effect against rising prices.

-Mismanagement at state-run oil firm Petrobras, including the country’s largest corruption scandal ever, boosted fuel prices despite the plunge in oil markets.

-And with rents, salaries and many other types of contracts adjusted according to past inflation rates, prices continue to go up even as the economy flounders.

Mexico, by contrast, has a much more flexible economy than Brazil’s.

Its relative openness to foreign trade helped it take advantage of deflationary pressures in major developed economies, most notably in the neighboring United States.

Mexico also worked to foster competition in key sectors such as telecommunications and energy.

The slack in the labor market has also played a role, economists said, after years of below-trend growth that only recently has shown evidence of picking up.

Both cases are extremes.

Elsewhere in Latin America, except for Venezuela and Argentina, inflation is somewhere in between Mexico’s and Brazil’s, in most cases running above but not far the official targets.

Such a split is also unlikely to remain as intense in 2016, according to Reuters Polls estimates. Brazil’s inflation rate is likely to slow down as the effect of higher government tariffs starts to fade; Mexico’s is likely to rise as an expected economic pick-up increases the pass-through from a falling currency.

But the underlying causes of such a wide disconnect will mostly remain in place.

Until Brazil gets past its political crisis and economic reforms are back in the agenda, inflation will remain a bogeyman putting constant pressure on the central bank to raise interest rates.

Governor Alexandre Tombini must now file a letter explaining how the bank missed its target so badly last year: the document, expected imminently, may shed more light on the bank’s strategy for what looks like another tough year for policymakers.